The Artist Who Broke Every Rule

Pablo Picasso 1/3 Mental Projector

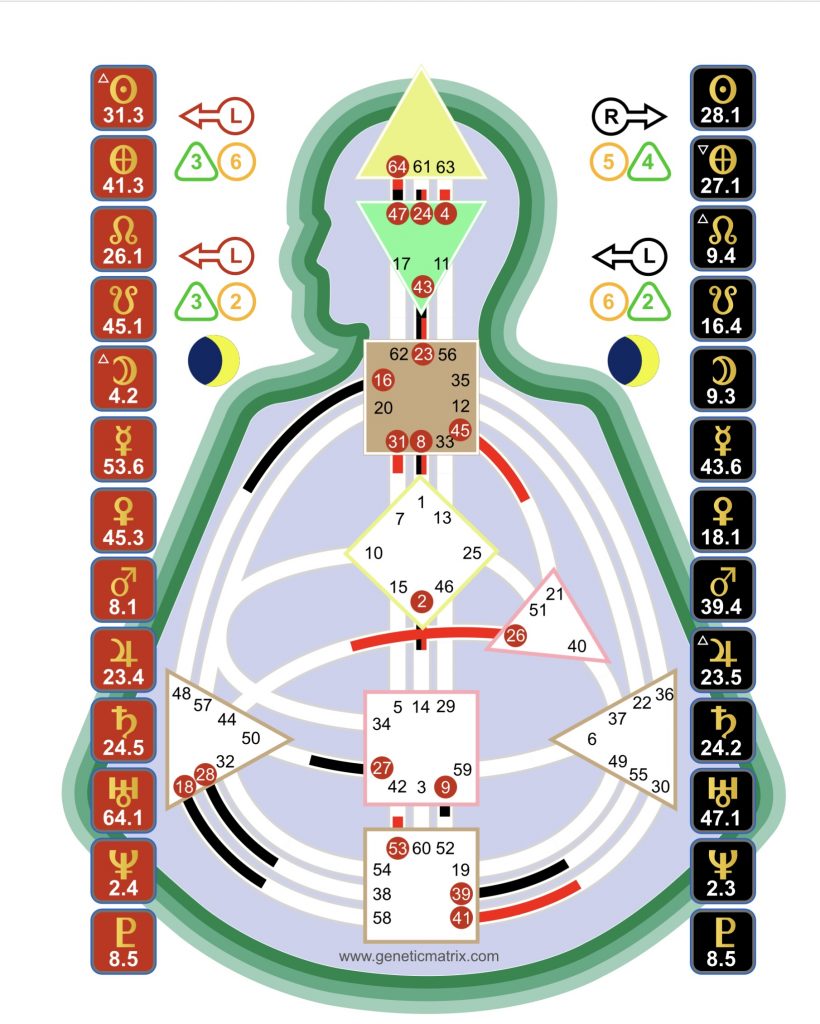

Pablo Picasso, born under the stars of Málaga, Spain on October 25, 1881, at 23:15, would become the twentieth century’s most revolutionary artist. Yet his Human Design reveals something surprising: he was a Mental Projector, a type typically associated with waiting, observing, and guiding rather than the explosive productivity for which Picasso became legendary. This apparent contradiction holds the key to understanding his genius.

The Mental Projector’s Paradox

To understand Picasso through Human Design is to grasp a fundamental paradox. Mental Projectors are not energy types. They don’t generate their own consistent life force like Generators or Manifestors. Instead, they’re designed to see deeply into the energy of others, to recognize patterns and possibilities that remain invisible to most. They succeed through recognition and invitation, not through forcing their will upon the world.

Yet Picasso produced an estimated 50,000 artworks in his lifetime. How does a non-energy type achieve such phenomenal output? The answer lies in the specific configuration of his design and his perfect alignment with it.

As a Mental Projector, Picasso possessed a rare gift: his Head, Ajna, and Throat centers were all defined and connected. This created a superhighway of mental energy, a constant pressure to think, conceptualize, and express. While his body might tire, his mind never stopped generating ideas that demanded manifestation. The Channel 47-64, known as the Channel of Abstraction, created perpetual mental pressure for abstract understanding that could only be relieved through creative expression. This explains why Picasso often said he didn’t seek but found – ideas came to him in an endless stream.

The Channel 23-43, the Channel of Structuring or Genius, gave him the ability to express unique, individual knowing. This is the channel of breakthrough insights, of seeing what others cannot see and expressing it in structured form. When we look at Cubism – the complete deconstruction and restructuring of visual reality – we see this channel in perfect expression.

The Investigator-Martyr’s Journey

Picasso’s profile, the 1/3 Investigator-Martyr, reveals the pattern that would define his entire artistic journey. The first line, the Investigator, demands deep study and solid foundation. We see this in young Pablo’s meticulous mastery of classical techniques under his father’s tutelage. Before he could break the rules, he had to know them intimately. This investigative nature never left him – before each revolutionary period, he would deeply study what came before, whether it was African masks before his African Period or classical mythology before his Neoclassical phase.

The third line, the Martyr, learns through trial and error, through bonds made and broken, through experimentation that often fails before it succeeds. This line doesn’t fear failure; it expects it as part of the learning process. Picasso’s willingness to abandon successful styles just as the world was catching up, his readiness to destroy yesterday’s masterpiece to create tomorrow’s revolution – this is the third line in action. He once said, “Every act of creation is first an act of destruction,” perfectly capturing the Martyr’s wisdom.

The Cross of the Unexpected

Perhaps most remarkably, Picasso carried the Right Angle Cross of the Unexpected 3. This incarnation cross represents one’s life purpose, the role they’re here to play in the collective story. Those who carry this cross are designed to bring unexpected transformation, to create dramatic shifts in perception that nobody sees coming. They don’t just change things; they change them in ways that shock, surprise, and ultimately transform collective understanding.

Consider Picasso’s major contributions to art: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which shattered centuries of perspective tradition; Guernica, which transformed how we see war and suffering; the invention of collage, which redefined what materials could constitute art. Each was unexpected, each transformed not just art but consciousness itself.

The Gates of Transformation

The specific gates in Picasso’s incarnation cross tell an even more detailed story. His conscious sun in Gate 28, line 1, “The Game Player,” speaks to embracing meaningful struggle and demanding from oneself what one demands from others. This is the energy of someone who transforms struggle into achievement, who sees life itself as a great game worth playing with total commitment. Picasso’s relentless self-reinvention, his refusal to rest on his laurels, his constant push against his own boundaries – this is Gate 28 in its highest expression.

His conscious earth in Gate 27, line 1, reveals how he grounded himself: through self-nourishment that might appear selfish to others. The earth position shows what stabilizes us, and for Picasso, it was the prioritization of his own creative needs above all else. His numerous relationships, often overlapping, his fierce protection of his creative time, his willingness to sacrifice personal relationships for his art – what seemed like selfishness was actually essential self-preservation, the necessary foundation for his gift to humanity. Yet this same gate, when lived from its shadow, can manifest as genuine cruelty. Gate 27 line 1 specifically speaks to “selfishness” as self-preservation, but Picasso often went beyond preservation into destruction of others for his own nourishment.

The unconscious sun in Gate 31, line 3, “The Leader through Example,” operated beneath his awareness. Picasso didn’t set out to be a leader; he didn’t write manifestos or establish schools. Yet he influenced more artists than perhaps any other figure in modern art. This gate creates influence through demonstration rather than explanation, leadership through doing rather than teaching. Every time Picasso entered a new period, artists worldwide followed, not because he told them to, but because he showed them what was possible.

His unconscious earth in Gate 41, line 3, “Decrease through Elimination,” reveals his unconscious pattern of grounding through reduction. Before each new artistic phase, Picasso would ruthlessly eliminate what no longer served. He didn’t gradually evolve from Blue Period to Rose Period to Cubism; he made sharp breaks, eliminating the old to make space for the new. This unconscious pattern of finding stability through elimination of the unnecessary gave him the freedom to constantly reinvent.

The Undefined Centers: Windows of Genius and Shadows of Cruelty

Picasso’s undefined centers were not weaknesses but windows through which he could experience and amplify the world around him. His undefined G Center, the center of identity and direction, made him a chameleon who could completely transform his artistic identity. Rather than having a fixed sense of self, he could become whoever his art needed him to be – the melancholic artist of the Blue Period, the revolutionary of Cubism, the classicist of his return to order. But this same undefined G Center also meant he had no fixed moral center, no consistent sense of who he was in relationship to others. He could be whoever the moment required, including someone cruel.

His undefined Emotional Solar Plexus meant he absorbed and amplified the emotions around him without being defined by them. The tragedy of his friend Casagemas’s suicide triggered the Blue Period; the joy of his relationship with Fernande Olivier sparked the Rose Period. He was an emotional mirror for his time, reflecting and amplifying collective feelings through his art. Yet this same undefined emotional center could make him emotionally unpredictable and unstable in relationships, amplifying not just beauty but also rage, jealousy, and cruelty without having his own emotional wave to regulate these amplifications.

The undefined Sacral Center explains his need for muses and constant companions. Without his own consistent life force energy, he needed to be around others who could provide that energy. This wasn’t weakness but design – he was meant to guide and direct energy, not generate it. His famous statement, “I don’t seek, I find,” perfectly captures the Projector’s strategy of waiting for life to come to them rather than chasing after it.

The Muses: Energy Vampirism by Design

Picasso’s relationship with his muses reveals perhaps the darkest expression of his Human Design. As a Mental Projector with an undefined Sacral Center, he literally could not generate his own life force energy. He needed others – specifically, he needed women with defined Sacral Centers who could provide the raw energy he would then direct into his art. This wasn’t romantic; it was vampiric by design.

His muses – Fernande Olivier, Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot, Jacqueline Roque – were not just inspirations but energy sources. He would drain them, use them up, and when they were depleted or no longer served his artistic vision, he would discard them, often cruelly. Dora Maar’s descent into madness, Marie-Thérèse’s suicide, Jacqueline’s suicide after his death – these weren’t coincidences but the devastating consequences of being an energy source for a Mental Projector who had learned to take without giving back.

His famous quote, “Women are machines for suffering,” reveals his conscious awareness of this dynamic. As a Projector, he could see deeply into others’ energy, but without emotional definition, he couldn’t truly empathize with their pain. His undefined Ego Center meant he constantly needed to prove his worth and power, often through domination of others. Combined with his Gate 27 line 1’s theme of self-preservation at any cost, he created a pattern of relationships that were fundamentally extractive.

The 3rd line in his profile, the Martyr, is also about bonds made and broken. But Picasso lived this from its shadow – instead of learning from broken bonds, he seemed to relish the breaking itself. “Every time I change wives I should burn the last one. That way I’d be rid of them. They wouldn’t be around to complicate my existence,” he once said. This isn’t just misogyny; it’s the shadow expression of someone who needed others’ energy to survive but resented that dependency.

Perhaps most intriguingly, Picasso had no inner authority. In Human Design, inner authority is our internal decision-making compass. Without it, Picasso had no consistent internal guide saying “yes” or “no.” This made him extraordinarily sensitive to external feedback and recognition, explaining his notorious sensitivity to critics despite his towering success. Yet it also freed him from internal resistance. Without an inner authority questioning or second-guessing, he could act on his mental impulses with remarkable freedom.

This lack of inner authority meant Picasso needed external sounding boards – his numerous companions, patrons, and fellow artists weren’t just social connections but essential elements of his decision-making process. He needed to hear his ideas reflected back, to see his work through others’ eyes, to feel the recognition that told him he was on the right track.

The Evolution Toward Legacy

Picasso’s North Node in Gate 26, “The Great Accumulation,” points to his evolutionary direction – what he was growing toward throughout his life. This gate is about managing and accumulating resources for great undertakings. In his youth, Picasso was notorious for his poverty and disregard for material concerns. But as he evolved, he became increasingly strategic about accumulating not just wealth but artistic legacy. By his later years, he had become one of the wealthiest artists in history, with vast collections of his own work that he carefully managed.

This wasn’t greed but evolution – he was growing into his design’s calling to accumulate resources for a purpose greater than immediate expression. Every painting he kept, every sketch he preserved, was part of building a legacy that would influence art for generations.

The Secret of His Energy

So how did a Mental Projector maintain such extraordinary productivity? The answer lies in perfect alignment. Picasso received recognition early and continuously throughout his life – the essential fuel for any Projector. From his first exhibitions in Barcelona to his death at 91, he was recognized, invited, celebrated. This recognition didn’t just feed his ego; it literally gave him access to energy he couldn’t generate alone.

His mental definition meant that while his body might tire, his mind never stopped. The pressure in his Head Center to answer questions, the conceptualizing power of his Ajna, the expressive force of his Throat – these created a perpetual mental motion machine that demanded expression. His Channel 47-64 generated constant abstract mental pressure that could only be relieved through creation. He wasn’t choosing to be prolific; his design demanded it.

Furthermore, Picasso intuitively surrounded himself with Generator types – people with defined Sacral centers who had the life force energy he lacked. His numerous relationships weren’t just romantic entanglements but energetic necessities. In the presence of these energy types, he could access and direct their life force toward his creative vision. But this same dynamic that fueled his art destroyed his lovers. He once told Françoise Gilot, “For me there are only two kinds of women: goddesses and doormats.” This binary view perfectly captures how a Mental Projector in shadow sees energy sources – either to be worshipped when fresh and full of energy (goddesses) or to be discarded when depleted (doormats).

His undefined Ego Center created an insatiable need to prove his value and power. Without a defined sense of self-worth, he had to constantly demonstrate his dominance. “Whenever I see you, I want to devour you. Or pull you into my lungs. Or merge with you. Or possess you,” he told one lover. This isn’t love; it’s the undefined Ego’s desperate attempt to feel valuable by possessing what it perceives as valuable.

The Perfect Storm of Genius

Picasso’s Human Design reveals not a contradiction but a perfect storm of elements aligned for revolutionary artistic expression. His Mental Projector type gave him the penetrating vision to see what others couldn’t. His 1/3 profile provided the methodology – deep study followed by fearless experimentation. His Right Angle Cross of the Unexpected ensured his contributions would transform collective consciousness in ways nobody anticipated.

His defined mental centers created unstoppable mental pressure for expression, while his undefined centers made him a perfect amplifier of his time’s emotional and spiritual currents. His lack of inner authority freed him from internal resistance while making him exquisitely sensitive to the external recognition that fueled his work.

Lessons from the Master’s Design

What can we learn from Picasso’s design? For Projectors, his life demonstrates the extraordinary power that comes from waiting for recognition and invitation rather than forcing outcomes. His success came not from pushing against resistance but from responding to the invitations that constantly came his way – from materials, from patrons, from the art world itself.

For those with the 1/3 profile, Picasso shows the importance of honoring both aspects – the deep study that creates foundation and the experimental courage that builds upon it. His failures weren’t failures at all but necessary steps in the learning process that the third line requires.

For all of us, Picasso’s example reveals that our greatest contributions come not from fighting against our design but from aligning with it completely. He didn’t succeed despite being a Mental Projector; he succeeded because he was one, living out his design with an unconscious perfection that allowed his purpose – bringing the unexpected – to flower fully.

The Eternal Revolutionary

In the end, Pablo Picasso’s Human Design chart reads like a blueprint for artistic revolution. Every aspect, from his Mental Projector type to his Right Angle Cross of the Unexpected, aligned to create an artist who could see reality from angles others couldn’t imagine, who could destroy yesterday’s certainties to birth tomorrow’s possibilities.

His famous quote, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up,” takes on new meaning through the lens of Human Design. Children naturally live their design before conditioning teaches them to be someone else. Picasso’s genius lay not just in his artistic ability but in his unconscious capacity to remain true to his design throughout his entire life.

He didn’t seek; he found – the perfect expression of a Projector waiting for life’s invitations. He didn’t explain; he demonstrated – the unconscious leadership of Gate 31. He didn’t gradually evolve; he revolutionized through elimination – the wisdom of Gate 41. He didn’t create despite struggle; he transformed struggle into achievement – the gift of Gate 28.

Pablo Picasso lived his design so perfectly that he became its highest expression, showing us that our greatest masterpiece is not what we create but how we live when we’re aligned with who we truly are. In breaking every rule of art, he followed the only rule that matters: be yourself, completely, unapologetically, revolutionary, creative.